Renewing Canada’s Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program

This document gives an overview of the current challenges facing the Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program. It is a 4-page document, but you can use the first page by itself.

This document gives an overview of the current challenges facing the Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program. It is a 4-page document, but you can use the first page by itself.

The National Human Trafficking Assessment Tool screens for elements that may indicate the possibility of human trafficking. This tool is meant to help guide first-contact service providers across Canada in identifying and responding to situations of human trafficking.

This file includes both Part 1 and Part 2 of the assessment tool.

Know a person or a group who may be interested in joining a vibrant national network of 200 member organizations and individuals working together for the rights of refugees and newcomers? Share these reasons to join the Canadian Council for Refugees with them.

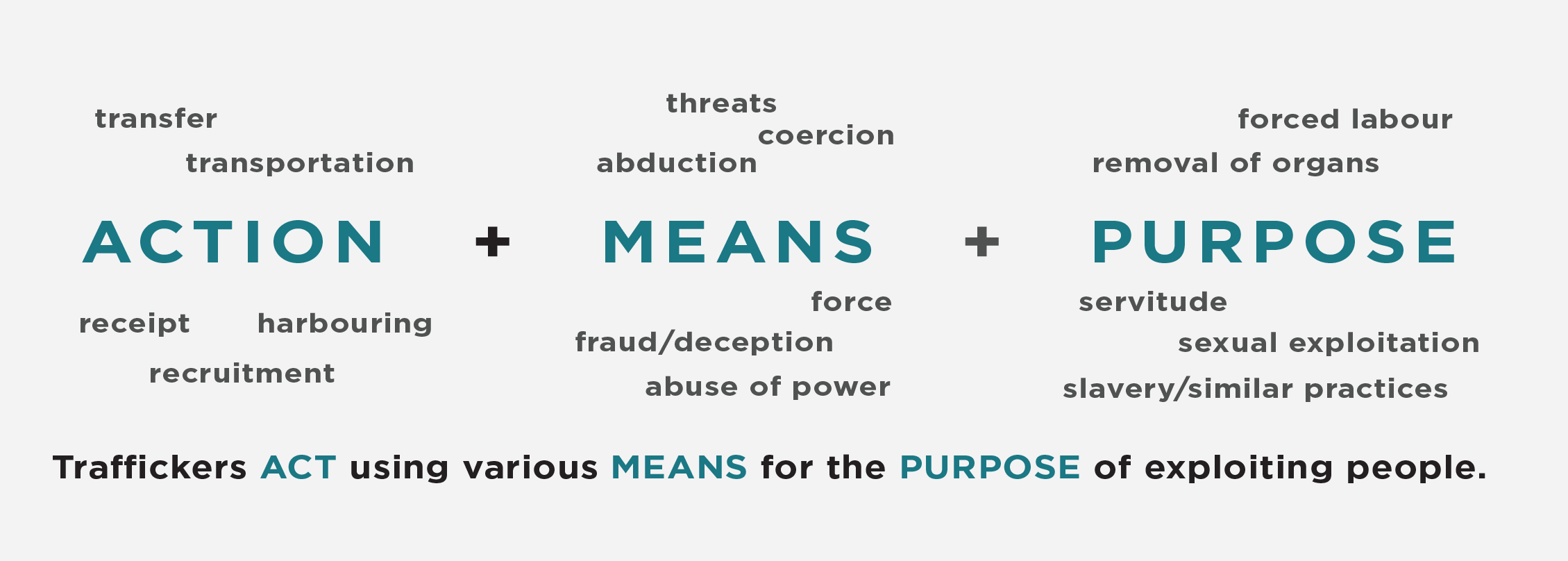

Trafficking in persons occurs when someone obtains a profit from the exploitation of another person by using some form of coercion, deception or fraud. Exploitation can take many different forms, including through forced labour in various areas such as the service, manufacturing, agricultural or construction sectors, through domestic work, and through work in the sex industry/prostitution. Regardless of the form of exploitation, trafficking in persons is a violation of a person’s basic human rights and it affects men, women and children.

This document aims to give information about how trafficking for labour exploitation can take place in Canada.

Trafficking for forced labour happens in a context of both global and local economic inequalities where many people are looking for ways to better protect and provide for themselves and their families.

Trafficking for forced labour happens in a context of both global and local economic inequalities where many people are looking for ways to better protect and provide for themselves and their families.

Around the world, approximately 21 million people are in a situation of forced labour. Most of these individuals are exploited by private individuals or businesses. A minority of people are forced to work by state entities. Women are overrepresented among forced labourers globally.[1]

Root causes of trafficking are often socio-economic or political. Poverty, conflicts, inequalities (including based on gender) and persecution are among the common contexts. While many people find themselves in situations of forced labour in their home communities, these root causes often push people to migrate in search of opportunities.

Increasingly restrictive immigration rules worldwide make it more difficult for people to migrate safely and make many migrants more vulnerable. Traffickers take advantage of these situations by exploiting the very limited options and lack of legal and social protections that are available to migrants.

Trafficking for the purpose of labour exploitation takes place when some means (including taking advantage of a person’s particular vulnerabilities) are used as a way of controlling someone in order to cause them to believe that they have no choice but to carry out a specific work or service.

Trafficking for the purpose of labour exploitation takes place when some means (including taking advantage of a person’s particular vulnerabilities) are used as a way of controlling someone in order to cause them to believe that they have no choice but to carry out a specific work or service.

The following shows what the various elements involved in labour trafficking might look like concretely.

An action whereby a person is:

A means whereby a person:

Exploitation, whereby a person is:

The people involved are not always just the employer or recruiter: acquaintances, neighbours and family members can also play a role.

Migrant workers and labour trafficking

In recent years, Canada has increasingly shifted its focus from permanent to more precarious temporary immigration. More workers are now being brought into Canada on a temporary basis with fewer rights than other workers to fill labour needs. These conditions and the lack of employment options available to them have made migrant workers extremely vulnerable to abuse and exploitation.

Trafficking in persons is the most extreme form of exploitation faced by migrant workers in Canada.

In Canada, trafficking for the purpose of labour has predominantly affected migrant workers. Those most affected by abuse and exploitation often come with valid work permits under the “low-skilled” streams of the Temporary Foreign Workers Program (TFWP), including the Low-wage and Primary Agricultural Streams and the Live-in Caregiver Program. Temporary Foreign Workers employed under these streams may be employed in restaurants, hotels or other hospitality services, on farms, in food preparation, in construction or in manufacturing, as well as in domestic work.

Vulnerabilities of Temporary Foreign Workers to trafficking in persons

The TFWP conditions place migrant workers in a situation where they are vulnerable to exploitation and trafficking. These conditions include:

Unfortunately, the changes introduced to the TFWP in June 2014 do little to strengthen protection measures for workers. Although some enforcement and monitoring measures have been added, the program continues to rely overwhelmingly on a complaints system that migrant workers are unlikely to use as this can still lead to deportation.

The shift towards more restrictive immigration policies in Canada has also created additional opportunities for people to be trafficked for the purpose of forced labour, by creating additional vulnerabilities that traffickers take advantage of.

Refugee claimants and labour trafficking

Some trafficked persons are forced by their traffickers to make a refugee claim, which is either meant to fail or is not pursued, so that the person is subject to removal. This facilitates traffickers’ ability to threaten and control trafficked persons in order to exploit their labour in different ways.

Recent changes to the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act bar people whose refugee claims have been rejected, withdrawn or abandoned, from applying for status, including the Temporary Resident Permit intended for victims of trafficking.[3] This has made it harder for trafficked persons to escape their traffickers and easier for traffickers to control them through threats of denunciation and deportation.

In 2010, 23 Hungarian men were trafficked to Canada. They were forced to make refugee claims, their documents were taken away and they were made to work on construction sites up to seven days a week without pay and to participate in criminal activities. They were threatened and some were physically assaulted. They were monitored, controlled and forced to live in the basement of their traffickers’ homes.

Had they faced the new legal barriers, they likely would not have received protection in Canada.

Family and domestic situations

Trafficking for forced labour also takes place in situations where a person is forced into domestic servitude by family members or by others outside the family. Such cases can include:

Children forced to work at home or exploited in other ways;

Children forced to work at home or exploited in other ways;Labour trafficking and precarious immigration status

People with insecure immigration status or no status at all are particularly vulnerable to trafficking for their labour. Whether they enter as a Temporary Foreign Worker, a refugee claimant, a student, a tourist or irregularly, traffickers may take advantage of their limited rights in Canada and the threat of detention and deportation, to force them to carry out work.

Due to changes in immigration policy, more people are in Canada with temporary and precarious status.

Possible solutions

The risk of trafficking can be reduced, and recourses for those who are trafficked improved by:

[1] International Labour Organization (ILO) 2012 Global Estimate of Forced Labour: http://bit.ly/1wreu9s.

[2] See Profiting from the Precarious: How recruitment practices exploit migrant workers, Metcalf Foundation, available online: http://bit.ly/QnrPBt.

[3] Canadian Council for Refugees, Access to Protection for Trafficked Non-Citizens: ccrweb.ca/en/protection-trafficked-persons

[4] Canadian Council for Refugees, Conditional Permanent Residence: ccrweb.ca/en/conditional-permanent-residence

[5] See Resource Information Guide to Human Trafficking Systems through Forced Marriages, South Asian Women’s Centre (SAWC): ccrweb.ca/en/resource-information-guide-human-trafficking-forced-marriages

The CCR has had an active campaign for the rights of migrant workers in Canada for the last ten years. The campaign has focused on the protection of migrant workers’ rights in Canada, and their access to permanent residence and to services. Since temporary labour migration is a global phenomenon, the CCR is beginning to get involved in migrant justice activities outside of Canada’s borders. Let’s take a closer look at the global dynamics of labour migration...

In recent years, it has become harder for newcomers to get Canadian citizenship. Increasingly difficult tests, more costly applications, additional requirements, longer waits and frustrating red tape have stood in the way of newcomers becoming citizens and thus being able to participate fully in Canadian society with all rights. These barriers are having a disproportionate impact on more vulnerable newcomers, such as refugees and more isolated or low-income newcomers.

Canada has traditionally encouraged newcomers to become citizens, as a way to strengthen our society and promote the integration of newcomers. Now citizenship is increasingly being presented as an exclusive reward to be given only to those who best overcome the hurdles of integration and satisfy economic criteria.

Since 2012, applicants for citizenship must provide, at their own expense, proof of their knowledge of English or French. Previously, their language skills were tested as part of the citizenship application process.

Providing acceptable proof can be difficult:

The new rules cause special problems for newcomers who have difficulties learning English or French:

If Bill C-24 passes, more people will have to meet language requirements, both younger and older applicants than is currently the case.

Citizenship fees were doubled as of February 2014 (from $200 to $400). This represents a lot of money for someone on a low income, such as a young student or a single-parent family.

Some people may not apply for lack of money.

Since May 2012, the government has asked many more applicants to fill in the very detailed Residence Questionnaire (RQ). Some applicants spend weeks tracking down the information requested, and then must wait months before institutions supply the documents. The time allowed to respond to the questionnaire is less than the time generally needed to gather all the documents. Some of the documents cost money to obtain.

Citizenship applicants have reported feeling discouraged when they are given the RQ – it can make them feel as though they are being regarded as suspicious or fraudulent, and sends an unwelcoming message.

Due to backlogs, citizenship applicants currently face delays of 2-3 years while their applications are processed. The wait is even longer for those who must complete the Residence Questionnaire.

This means that newcomers can’t participate fully in Canadian society for years, even though they meet all the legal requirements for citizenship.

Many applicants report frustration with the administrative process. A large proportion of applications are returned as incomplete, sometimes in error. It is difficult to communicate with officials about the progress of one’s application.

Recent changes to the law mean that people in Canada who have refugee status can more easily lose their right to remain in Canada.

If a person who came as a refugee shows on their application for Canadian citizenship that they travelled to their home country, this information may be used to launch an application for cessation. The potential consequence is loss of permanent residence and deportation from Canada.

This means that applying for citizenship may be risky for refugees, thus deterring full integration into Canadian society.

“I worry that all these barriers to becoming a citizen will undo one of the things Canada has been good at: making newcomers feel welcome and encouraging them to be full members of Canadian society.” Loly Rico, CCR President

These obstacles in the path to citizenship are having a damaging effect on the integration of newcomers, who are denied the rights of full participation, notably the right to vote. For refugees, who have no other country, the effect is particularly severe.

A trifold pamphlet about the Walk with refugees (15 - 21 June 2015). Includes ideas to get involved and ways to continuing walking with refugees throughout the year.

Many different terms are used to describe refugees and immigrants. Some have particular legal meanings, some are mean and offensive. Using terms properly is an important way to treat people with respect and advancing an informed debate on the issues.

Refugee – a person who is forced to flee from persecution and who is located outside of their home country.

Convention refugee – a person who meets the refugee definition in the 1951 Geneva Convention relating to the Status of Refugees. This definition is used in Canadian law and is widely accepted internationally. To meet the definition, a person must be outside their country of origin and have a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.

Refugee claimant or Asylum Seeker – a person who has fled their country and is asking for protection in another country. We don’t know whether a claimant is a refugee or not until their case has been decided.

| 'Claimant’ is the term used in Canadian law. |

Resettled refugee – a person who has fled their country, is temporarily in a second country and then is offered a permanent home in a third country. Refugees resettled to Canada are selected abroad and become permanent residents as soon as they arrive in Canada.

| Resettled refugees are determined to be refugees by the Canadian government before they arrive in Canada. Refugee claimants receive a decision on whether they are refugees after they arrive in Canada. |

Protected person – according to Canada’s Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, a person who has been determined to be either (a) a Convention Refugee or (b) a person in need of protection (including, for example, a person who is in danger of being tortured if deported from Canada).

Internally displaced person – a person who is forced to leave their home, but who is still within the borders of their home country.

Stateless person – a person that no state recognizes as a citizen. Some refugees may be stateless but not all are. Similarly, not all stateless people are refugees.

You may also hear… Political refugee, Economic refugee, Environmental refugee – these terms have no meaning in law. They can be confusing because they incorrectly suggest that there are different categories of refugees.

| WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A REFUGEE AND AN IMMIGRANT?

A refugee is forced to flee for their lives. An immigrant chooses to move to another country. |

Immigrant – a person who has settled permanently in another country.

Permanent resident – a person granted the right to live permanently in Canada. The person may have come to Canada as an immigrant or as a refugee. Permanent residents who become Canadian citizens are no longer permanent residents.

Temporary resident – a person who has permission to remain in Canada only for a limited period of time. Visitors and students are temporary residents, and so are temporary foreign workers such as agricultural workers and live-in caregivers.

Migrant – a person who is outside their country of origin. Sometimes this term is used to talk about everyone outside their country of birth, including people who have been Canadian citizens for decades. More often, it is used for people currently on the move or people with temporary status or no status at all in the country where they live.

Economic migrant – a person who moves countries for a job or a better economic future. The term is correctly used for people whose motivations are entirely economic. Migrants’ motivations are often complex and may not be immediately clear, so it is dangerous to apply the “economic” label too quickly to an individual or group of migrants.

Person without status – a person who has not been granted permission to stay in the country, or who has stayed after their visa has expired. The term can cover a person who falls between the cracks of the system, such as a refugee claimant who is refused refugee status but not removed from Canada because of a situation of generalized risk in the country of origin.

You may also hear... Illegal migrant/illegal immigrant/Illegal – these terms are problematic because they criminalize the person, rather than the act of entering or remaining irregularly in a country. International law recognizes refugees may need to enter a country without official documents or authorization. It would be misleading to describe them as “illegal migrants”. Similarly, a person without status may have been coerced by traffickers: such a person should be recognized as a victim of crime, not treated as a wrong-doer.

Download and print this document for your own use and for distribution.

Distinguishes between common terms used to talk about refugee and immigrants in Canada and around the world, 2 pages. 2010.