On 4 June 1969, Canada belatedly signed the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, 18 years after it was adopted by the United Nations, and 15 years after it entered into force.

On 4 June 1969, Canada belatedly signed the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, 18 years after it was adopted by the United Nations, and 15 years after it entered into force.

In the 40 years since Canada became a party to the Refugee Convention, it has gained the enviable reputation of being a world leader in protecting refugees.

In fact, there has been good and bad in Canadian responses to refugees, both before and after signing the Refugee Convention.

|

| Doukhobor women breaking the prairie sod by pulling a plough themselves, Thunder Hill Colony, Manitoba. c 1899. Library and Archives Canada,C-000681. |

|

MP Samuel Jacobs spoke in favour of “those who are obliged to leave their own countries in Europe by reason of religious and social persecution. Now, this country, it seems to me, should be the haven of rest for people of that kind, and we ought to have our doors wide open for all those who flee from persecution, social or otherwise, in European countries.” 30 March 1921, House of Commons

|

|

| The St. Louis, surrounded by smaller vessels in the port of Havana, 1938. Herbert Karliner. Source: US Holocaust Memorial Museum. Photograph #88358 |

| “Ever since the war, efforts have been made by groups and individuals to get refugees into Canada but we have fought all along to protect ourselves against the admission of such stateless persons without passports, for the reason that coming out of the maelstrom of war, some of them are liable to go on the rocks and when they become public charges, we have to keep them for the balance of their lives” (F.C. Blair, Director, Immigration Branch, 1938) |

| “as human beings we should do our best to provide as much sanctuary as we can for those people who can get away. I say we should do that because these people are human and deserve that consideration, and because we are human and ought to act in that way.” Stanley Knowles, MP, House of Commons, 9 July 1943 |

|

The Canadian delegate and chair of the committee drafting the refugee convention was put in a very uncomfortable position by the last-minute withdrawal of support by his government. He tried to explain the consequences to the External Affairs Minister: “Any turning back on our part now might create very unhappy situation. We have been regarded throughout as taking forward attitude, somewhat in contrast to that of the United States, concerning whose signature there has always been doubt and in consequence some little undercurrent of feeling among other delegations. It would in addition, in my opinion, weaken seriously the job of the High Commissioner for Refugees with whom I hope to have some discussion tomorrow.” Telegram, Permanent Representative to European Office of United Nations to Secretary of State for External Affairs, July 3rd, 1951

For more information about Cabinet concerns, see CABINET DOCUMENT NO. 178-51, Ottawa, June 14th, 1951 |

| Leslie Chance (left) of Canada at the Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Status of Refugees and Stateless Persons, Geneva, July 1951. Mr Chance, on behalf of Canada, chaired the committee that drafted the conventions under discussion. Credit: UNHCR |

|

| One of several organizations helping Hungarian refugees resettle to third countries. 1956. © UN 56817 |

| “By the 1970’s it was widely held that Canada was then and always had been a haven for the oppressed. In retrospect the public imagination turned a select series of economically beneficial refugee resettlement programs into a massive and longstanding Canadian humanitarian resolve on behalf of refugees.” Harold Troper |

|

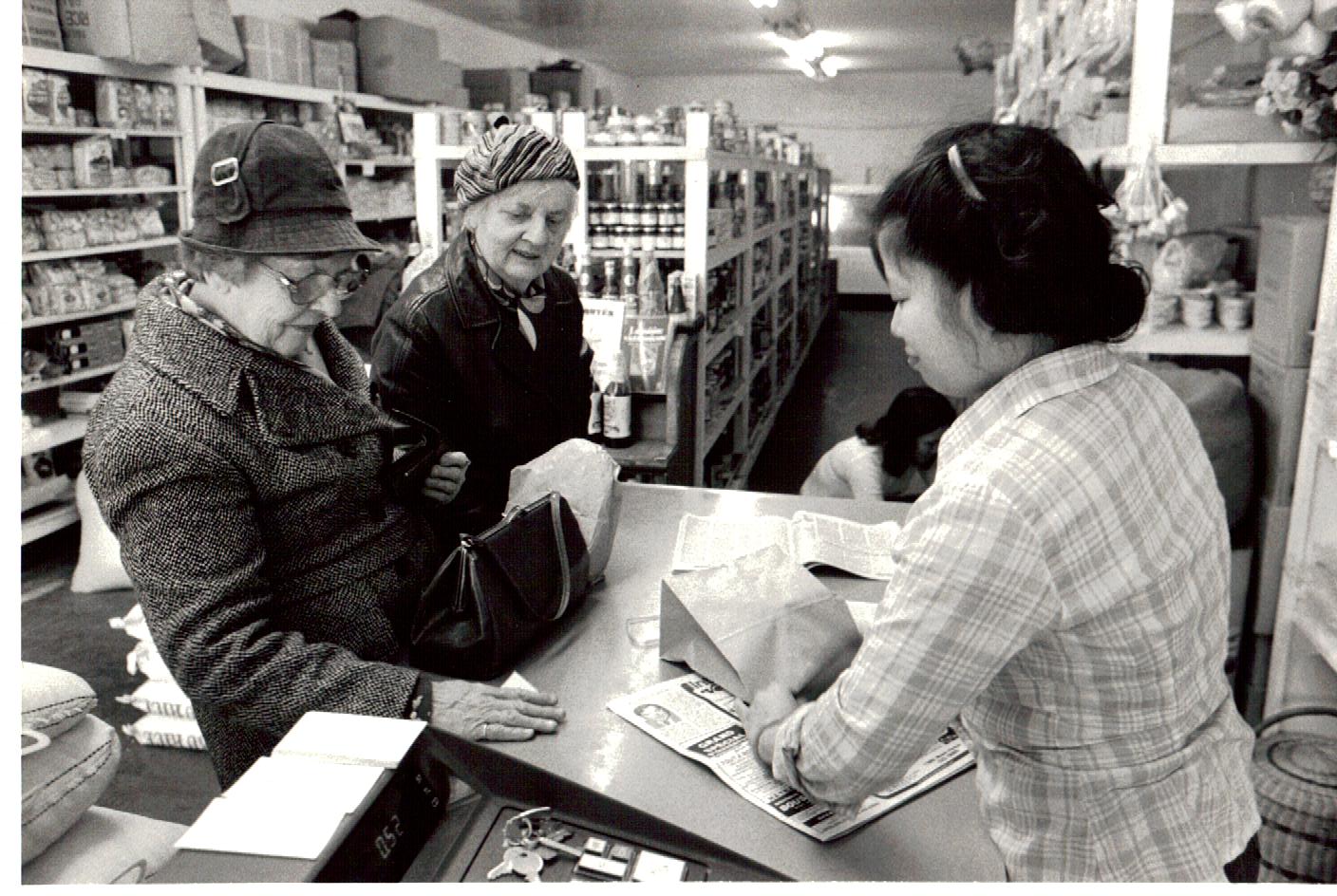

| A Vietnamese refugee working in a supermarket in Montreal. 1979. Photo credit: UNHCR/9090/H. Gloaguen/VIVA |

The people of Canada were awarded the Nansen medal by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, in “recognition of their major and sustained contribution to the cause of refugees”.

The people of Canada were awarded the Nansen medal by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, in “recognition of their major and sustained contribution to the cause of refugees”.