Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution.

- Article 14 (1), Universal Declaration of Human Rights

|

| Matthew House Toronto staff, October 2013. Matthew House is one of many members of the Canadian Council for Refugees. |

Who is a refugee?

How do refugees come to Canada?

Resettlement to Canada

Refugee claims in Canada

Family reunification

Statelessness

Access to citizenship

Who is a refugee?

Refugees are people who are forced to leave their home countries because of serious human rights abuses.

The right to asylum from persecution is an international human right. It is guaranteed by the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (the “Refugee Convention”).

According to this Convention, a refugee is a person:

who is outside his or her home country and who has a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.

The Convention also spells out the key responsibilities of states towards refugees, which include the obligation not to send refugees back to the country where they face persecution. (This is known as the principle of “non-refoulement”).

|

The 1951 Refugee Convention was developed in the aftermath of the Second World War period. People were determined not to repeat the mistakes that occurred during the Holocaust, when many countries had failed to offer asylum to Jewish refugees, contributing to the death toll in the genocide (Canada, to our shame, was one of the worst offenders). Canada did not sign the Convention until 1969. |

Did you know...?

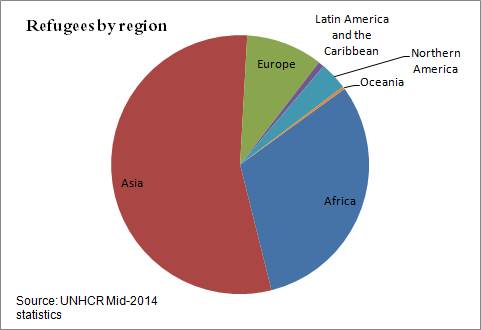

The vast majority of the world’s refugees are in the Global South. Only a tiny minority of refugees are found in Canada and the rest of the wealthiest countries.

How refugees come to Canada

Refugees can come to Canada in two ways:

- Resettlement (where refugees who are outside Canada are selected overseas and then travel to Canada). This is a discretionary response, for which we have a moral obligation.

- The refugee claim process (where refugees who are inside Canada or at Canada’s borders have their claim to refugee status determined in Canada).

Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.

- Section 7, The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

... the refugee program is in the first instance about saving lives and offering protection to the displaced and persecuted...

Paragraph 3 (2)(a), Objectives, Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

Resettlement to Canada

Every year thousands of refugees are resettled to Canada from another country where they are staying temporarily. They may be living in a refugee camp, in urban areas or trying to survive in a country where they have no status and few, if any, rights. They may even be in detention or facing a risk of forced return to persecution. For them, resettlement to a third country such as Canada represents the only available solution. Resettlement provides protection and a durable solution (in other words, a permanent home).

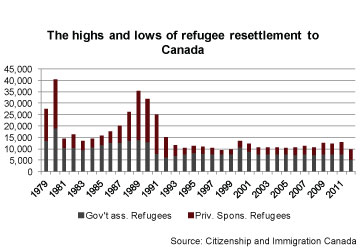

The Canadian refugee resettlement program is composed of two categories:

- Government-assisted refugees, who receive support on their arrival from the government.

- Privately sponsored refugees, who receive support from private groups.

- Be recognized as a refugee (or in a similar situation, as defined in the Canadian regulations)

- Not be barred on grounds of criminality, security risk, or danger to health

- Be considered capable of becoming “successfully established” in Canada

- Have no other reasonable prospect of a durable solution (that is they can’t go safely home, stay permanently with full rights in the country where they are or have an offer of resettlement to another country).

- Be supported financially, either by the government or by a private group.

|

| Bhutanese refugees seek answers to questions about resettlement so that they can make an informed decision about their future. Credit: Jesuit Refugee Service/USA |

Some examples of situations from which refugees have been recently resettled to Canada:

- Bhutanese refugees in Nepal. Displaced since the 1990s, these refugees have been living in camps. Over 5,000 have been resettled to Canada.

- Eritrean refugees in Cairo. Their physical and economic situation in Cairo is very precarious. Women in particular are at risk of sexual assault.

- Gay and lesbian refugees from Iran via Turkey.

The 1951 Refugee Convention was developed in the aftermath of the Second World War period. People were determined not to repeat the mistakes that occurred during the Holocaust, when many countries had failed to offer asylum to Jewish refugees, contributing to the death toll in the genocide (Canada, to our shame, was one of the worst offenders).

Canada did not sign the Convention until 1969.

Some things to celebrate about Canada’s resettlement program:Canada’s private sponsorship program allows citizens to provide protection and a new home to a greater number of refugees.

Countless Canadians have also benefitted from the program, through the opportunities it offers for personal relationships with people who have survived persecution in various corners of the globe. Private sponsors can identify the refugees that they wish to sponsor, including refugees they feel are being forgotten by others. |

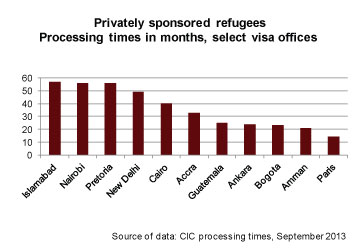

Some concerns about Canada’s resettlement program:

|

Since as refugees in Egypt, we cannot really integrate or have the right to work officially or access any services like other people in the country, I applied for sponsorship but even that did not work. [...] I cannot return home because I might be killed for my faith and I cannot stay in Egypt because there is no hope of ever living normally. I started the process for the Canadian sponsorship in the beginning of 2008 and I am still waiting, I am scared and I am losing hope.

Recent changes:

- Canada is moving from resettling refugees from many regions in the world to a more targeted approach, where only a few specific refugee groups will be resettled by the government.

- There are more restrictions on how many refugees private sponsors can resettle, particularly from Africa. On the other hand, private sponsors are encouraged to sponsor more refugees that the government has identified as priorities.

- Most privately sponsored refugees no longer have federal coverage for important health needs, such as medications and prosthetics.

Refugee claims in Canada

A person fleeing persecution who is at Canada’s borders or within the country can ask for Canada’s protection by making a refugee claim.

The claim process has three main steps:

1. Eligibility: A claim is not eligible if the claimant.

- made a previous refugee claim in Canada.

- has refugee status in another country.

- arrived at the US-Canada border (with some exceptions)

- is inadmissible on certain security and criminality grounds.

2. Refugee determination

Eligible claims are referred to the Refugee Protection Division of the Immigration and Refugee Board, which determines whether the claimant:

- is a Convention refugee; or

- faces a danger of torture, or

- faces a risk to their life or of cruel and unusual treatment or punishment (and the risk is not generally faced by others and is not caused by inadequate health care).

If the IRB accepts the claim, the claimant becomes a Protected Person and can apply for permanent residence. They can include on the application immediate family members overseas).

3. Refugee Appeal

A claimant who is refused may be able to appeal to the Refugee Appeal Division of the Immigration and Refugee Board. However, many claimants are barred from making an appeal. The government can also appeal a decision by the Refugee Protection Division that the claimant is a refugee.

|

On 4 April 1984 the Supreme Court of Canada issued the Singh decision, recognizing that the Canadian Charter guarantees refugee claimants’ right to a fair refugee hearing. 4 April is celebrated each year as Refugee Rights Day in Canada. The UN Convention against Torture, to which Canada is signatory, prohibits the return of anyone to a country “where there are substantial grounds for believing that he would be in danger of being subjected to torture.” |

Some things to celebrate about Canada’s refugee determination system: |

|

Refugee determination in Canada is done by an independent, quasi-judicial tribunal (the Immigration and Refugee Board)

|

| Canada has long recognized claims by people persecuted on the basis of their gender or sexual orientation. In 1993 Canada became the first country in the world to adopt Gender Guidelines for refugee claims, and set a precedent for other countries. |

|

Although there are many gaps in coverage, legal aid is available to some refugee claimants, which means they can hire a lawyer to help ensure their claim is fully and fairly presented.

|

Major changes were made to Canada’s refugee system in 2012:

- Refugee claimants now face very short timelines to present their claims.

- Claimants from ‘Designated Countries of Origin’, so-called ‘safe’ countries, face even shorter timelines and have no right of appeal.

- Refused refugee claimants cannot apply for pre-removal risk assessment (PRRA) or humanitarian and compassionate consideration for one year.

- Some refused refugee claimants finally have access to a full appeal on the merits, if their claim is refused (although many are denied this right.

- The law now allows the Minister of Public Safety to designate groups of two or more people, based on how they arrived. Designated Foreign Nationals face mandatory detention and a 5 year bar on family reunification, among other rights restrictions.

- Cuts to the Interim Federal Health Program have drastically reduced access to health care for refugee claimants.

Some other concerns about Canada’s treatment of refugee claimants: |

It has become increasingly difficult for refugees to get to Canada to make a claim here, because of barriers set up by the government. These measures (known as “interdiction” measures) include:

|

|

Some claimants, including children, are detained. It is very difficult to prepare yourself for a refugee hearing while in detention.

|

| Gaps in Canadian law mean that some people may be deported to face persecution or torture, or without consideration of the best interests of a child, contrary to Canada’s international legal obligations. |

Family reunification

Whether resettled to Canada or arriving as claimants, refugees need to be able to reunite quickly with their family. When refugees are forced to flee, parents are often separated from their children, spouses from each other. Sometimes, it is because, in the midst of danger, they run in different directions. Sometimes, it is because it is safer for only the family member most at risk to flee.

Reuniting families is good policy, both for the families that are reunited and for society as a whole.

One of the objectives (3(2)(f)) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act is:

to support the self-sufficiency and the social and economic well-being of refugees by facilitating reunification with their family members in Canada

When children are involved, family reunification is a basic human right:… applications by a child or his or her parents to enter or leave a State Party for the purpose of family reunification shall be dealt with by States Parties in a positive, humane and expeditious manner.

- Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 10(1)

Process for reuniting family members

Canadian law provides for reuniting only immediate family members: spouse or common-law partner (same sex or opposite sex) and dependent children.

For resettled refugees:

- Canadian policy is to resettle the whole family together if possible. When this is impossible (for example a family member’s whereabouts are unknown), there is the “One Year Window of Opportunity”, under which the remaining family member can come to Canada if their application is filed within one year of the refugee’s arrival in Canada.

For refugees who came as claimants:

- When accepted refugees apply for permanent residence, they can include immediate family members, whether they are in Canada or overseas.

Once they become permanent residents or citizens, refugees:

- Can sponsor certain family members in the Family Class. However, the income requirements make sponsorship beyond the reach of many who arrived in Canada as refugees.

|

| Quentin was barred by Regulation 117(9)(d) from reuniting with his family in Canada. As a member of the group that sponsored his family observed, “For the past two years I have been surprised, disappointed and grown more and more angry that an infant, born approximately four months before they departed for Canada, has been barred admission to this country.” Quentin was reunited with his family after more than 3 years. |

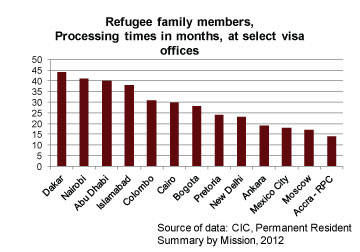

Some concerns about family reunification for refugees:

- Refugees often wait years to be reunited with spouse and children overseas, because of long delays in processing. Processing times are particularly long in Africa.

- Refugees, especially those from Africa, are often required to undergo DNA tests to prove the family relationship. DNA tests are costly and add to the delays.

- There are no provisions for refugee children in Canada to apply for reunification with their parents and siblings.

- Some family members, often young children, are “excluded family members”, according to Regulation 117(9)(d), because they were not examined by an immigration officer when the refugee became a permanent resident. The bar on reuniting with these family members is life-long, no matter what the explanation. This rule has led to children being separated from their parents for years.

- The government is proposing to reduce the maximum age of dependent children to 18 years (from 21), starting January 2014. This means that refugee parents will be forced to leave behind their young adult children, even though they may be at risk or have acted as surrogate parents.

|

|

According to a father waiting over four years to reunite his two teenager daughters who were separated from the rest of their family, “It’s more than a nightmare.” Contrary to popular belief…You cannot sponsor all your extended family. In fact, the law permits reunification with only a very limited range of family members. You cannot even sponsor your brother or sister (unless they are orphaned). Under a proposed, new rule you will not be able to sponsor children if they are older than 18. |

|

| Under Dominican law, all children born in Dominican territory have the right to Dominican citizenship. However, many children of Haitians are denied citizenship rights. Credit: Jesuit Refugee Service/USA |

Statelessness

Some refugees are stateless; others are not.

Many people are stateless but are not also refugees. These people are particularly vulnerable in Canada because Canada has no laws specifically to protect the rights of stateless persons.

A person is “stateless” if no State considers them a citizen.

States have specific obligations towards their citizens and grant citizens significantly more rights than non-citizens. Since no State recognizes them, stateless persons are deprived of many basic rights and have no State to protect them.

|

Some of the causes of statelessness:

The United Nations estimates that there are 12 million stateless persons in the world. |

Did you know...?In 2013, the United Kingdom introduced a new stateless determination procedure. Is this a model for Canada to follow? |

The 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons is very similar to the Refugee Convention and is intended to provide the same basic protections for stateless persons as the Refugee Convention does for refugees.

Canada has not signed this Convention.

2014 is the 60th anniversary of the Convention – a great opportunity for Canada to finally sign on!

Canada has recently resettled some 5,000 Bhutanese who have been stateless refugees in Nepal for over 15 years. They were disenfranchised by the Bhutanese government in the 1980s and forced to flee. Children born in the refugee camps have been stateless all their lives.

Access to citizenship

Most newcomers to Canada are interested in becoming citizens, but for most refugees acquiring Canadian citizenship is particularly important. Forced to flee a country where the government was unable or unwilling to protect them, refugees need the protection of a State, whether they are legally stateless or not.

Traditionally Canada has made it relatively easy for refugees and other newcomers to become citizens. But recently there have been increased barriers:

- Processing delays are extremely long (25-35 months). This means that even though the law says people can become citizens after living 3 years in Canada, in practice people must wait more than 5 years.

- Since November 2012, applicants must provide proof of their English or French skills, at their own expense. This can mean significant extra costs.

- Many applicants are required to fill out a very demanding Residence Questionnaire. It is costly and time-consuming to collect all the documentation requested, and these applicants face even longer delays.

|

The CCR celebrates its 35th birthday in 2013. Since 1978 the Canadian Council for Refugees has been working together on behalf of refugees and immigrants in Canada. It has established itself as a key advocate for refugee and immigrant rights in Canada, educating the public and putting issues onto the national agenda. |