|

The large backlog of claims in the refugee determination system is caused by the government’s failure to appoint sufficient Board members to make decisions.

In recent years, the Immigration and Refugee Board has been significantly short of members, at times lacking as many as a third of its members.

The Auditor General, in her March 2009 report, raised serious concerns over the shortfall and high turnover of Board members. She found that:

The high number of Board member vacancies at the IRB had a significant impact on the Board’s capacity to process cases on a timely basis. The inventory of unresolved cases has reached an exceptionally high level.1

The backlog is causing enormous hardship for refugees who are forced to wait years before receiving protection and being able to get on with their lives in security. Some refugees are separated from immediate family members overseas – during the wait there is no prospect of family reunification, even if their relatives are at risk.

"Allowing a backlog like the present one is an abuse of our refugee system. This will ultimately cost the taxpayer far more than processing the claims in a timely way, and it also ensures that people who are not refugees will remain in Canada for a long time." Dr Catherine Dauvergne, Canada Research Chair in Migration Law, UBC Faculty of Law

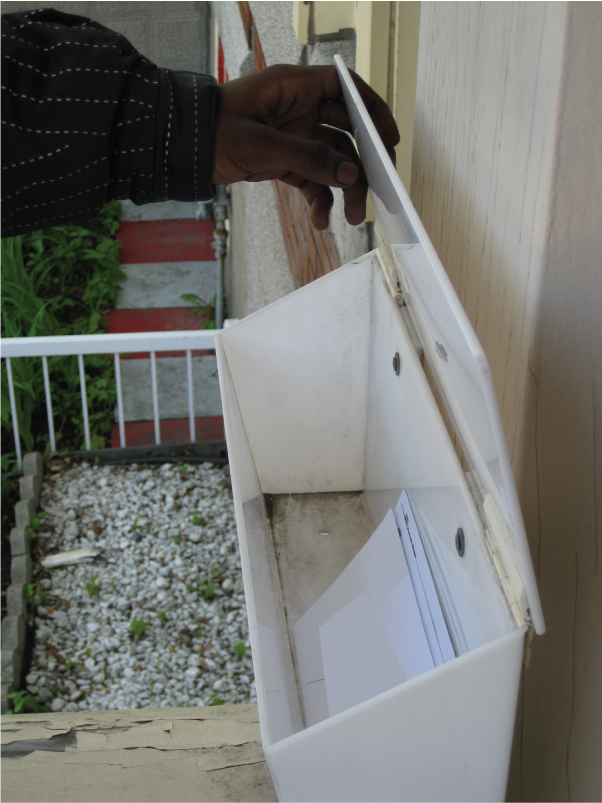

Prasant (not his real name) has been waiting for almost two years for his refugee claim to be determined – and he still doesn’t even know when the hearing will take place. The wait is agonizing because his wife and two children remain in danger in Nepal. Prasant can do nothing to reunite the family in safety until he has been accepted as a refugee.

Prasant was a businessman, social worker and political activist. He describes himself as a human rights defender and proponent of multiparty democracy. He fled Nepal because he was targeted by the Maoists, who tried to force him to join their party and support their activities. When he refused, they attempted to extort from him a huge sum of money which he did not pay, both because he couldn't and because he objected on principle to giving them any support.

His family is also at risk and has had to separate as a consequence: his wife is hiding with relatives, his two children are staying in residences attached to their high schools. His daughter is now 18 and finishing high school: Prasant does not know where she can go to live once she graduates. The family survives on money Prasant sends from his work in a factory in Toronto.

Prasant’s wife and children keep asking him “How long?” |

Another factor contributing to the backlog is the recent increase in the number of claims. There are many reasons why more people are making claims, but one reason is the fact that the government has allowed the backlog to develop. When the determination process is slow, there is an incentive for people to make a claim in Canada in order to work here for a few years, even if they expect that their claim will eventually be refused.

Historically, numbers of refugee claims rise and fall. When the numbers rise, the government needs to appoint additional decision-makers in order to avoid a backlog developing. The government has been doing exactly the opposite: creating a backlog by appointing insufficient members.

The system of appointing members through Governor-in-Council appointments has never worked well, because both the quality and timing of appointments are regularly and negatively affected by political considerations. The current system should be replaced by a merit-based,

non-political appointment system.

“It’s hard to communicate to the general public what refugees go through while waiting for the hearing date or the decision. Many get discouraged along the way and develop signs of depression. Some even speak of having thoughts of suicide. The wait is so stressful that by the day of the hearing many are worn down. They have been going through this unbearable state of waiting, not knowing where they’re going, where they’ll be.” Sylvain Thibault, Montreal City Mission

Papi fled to Canada from his home in North-West Africa in 2006, when he was just 17 years old. He spent 27 months, lonely and anxious, waiting for his refugee claim to be heard. He was in constant fear of deportation. He could not pursue his education. His family back home didn’t understand. “My father told me that I must have done something bad in Canada and that was why things were not moving forward for me. He stopped believing me. I felt even lonelier.” Papi was finally accepted as a refugee in 2009. Papi fled to Canada from his home in North-West Africa in 2006, when he was just 17 years old. He spent 27 months, lonely and anxious, waiting for his refugee claim to be heard. He was in constant fear of deportation. He could not pursue his education. His family back home didn’t understand. “My father told me that I must have done something bad in Canada and that was why things were not moving forward for me. He stopped believing me. I felt even lonelier.” Papi was finally accepted as a refugee in 2009. |

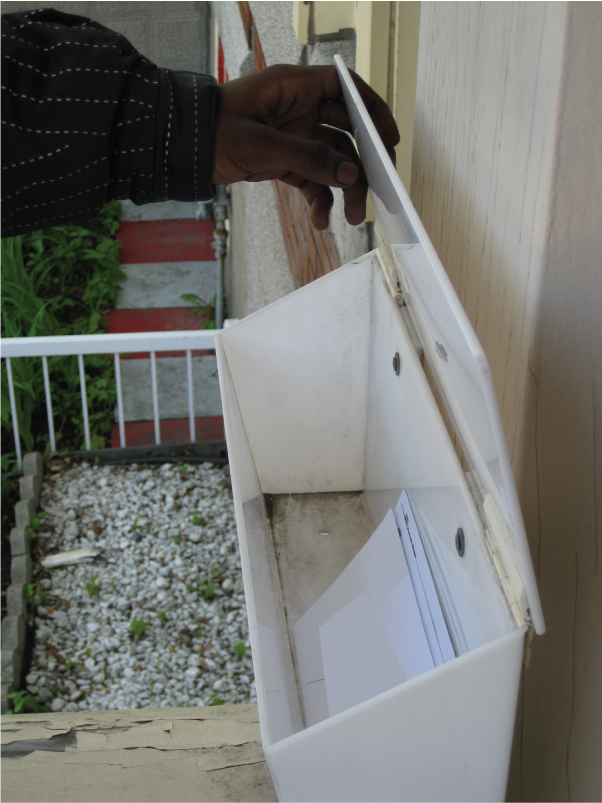

Cindy (not her real name) was in her mid-twenties when she made a refugee claim in Canada on her arrival in February 2007. She fled Nigeria because her family had discovered that she was gay – they accused her of bringing shame on the family by her sexual orientation and insisted that she submit to a “cleansing” process. Because her father was very influential, she could not find protection elsewhere in Nigeria, a country where homosexuality is illegal.

More than two years later, Cindy is still waiting for her refugee claim to be determined. She had been close to graduating in banking and financing when she fled Nigeria, but she is unable to return to school here until she is accepted as a refugee. Instead she is working for a security company.

Cindy struggled hard to get to Canada and has been working to support herself, finding a job as soon as possible after her arrival. She has fought for herself.

Her hearing is scheduled for July, 29 months after she arrived. |

|

Read

Read  Read

Read  Read

Read