Looking Back after Twenty Years

As a result,

the Canadian people themselves sponsored 34,000 of the 60,000 refugees

from Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam who arrived in 1979 and 1980 to begin

a new life in Canada. Twenty years later, it is worth remembering this

exceptional period of history and highlighting its lasting effects.

| In recognition of the compassionate response of thousands in Canada to the needs of refugees from Indochina and elsewhere, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees took the unprecedented step in 1986 of awarding its prestigious Nansen medal to the Canadian people themselves. |

The

Refugee Crisis in Southeast Asia

As the number of

people in the refugee camps in the region expanded rapidly in 1978 and

1979, the international community gradually recognized that only a massive

resettlement program would meet both the needs of the refugees themselves

as well as the concerns of the governments receiving them. Not only

was it clear that the refugees would not be able to return home in the

foreseeable future, but it also was apparent that local countries would

not take in many more refugees without substantial international support.

Political, economic, and social conditions were highly unstable in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam in the 1970s, leading to an exodus of over 3 million people from 1975 until well into the 1990s. Although the precise causes of the refugee movements were different in each country, the forms of persecution were similar.

Those who had worked for the defeated U.S.-backed regimes were singled out for harsh treatment, while others — particularly those of Chinese ancestry — were targeted because of their ethnicity. Many people were put into "re-education camps," moved to another part of the country against their will, or forced to work for the new government in power. On top of such widespread human rights abuses, continued violence both within and between states put the lives of thousands more at risk.

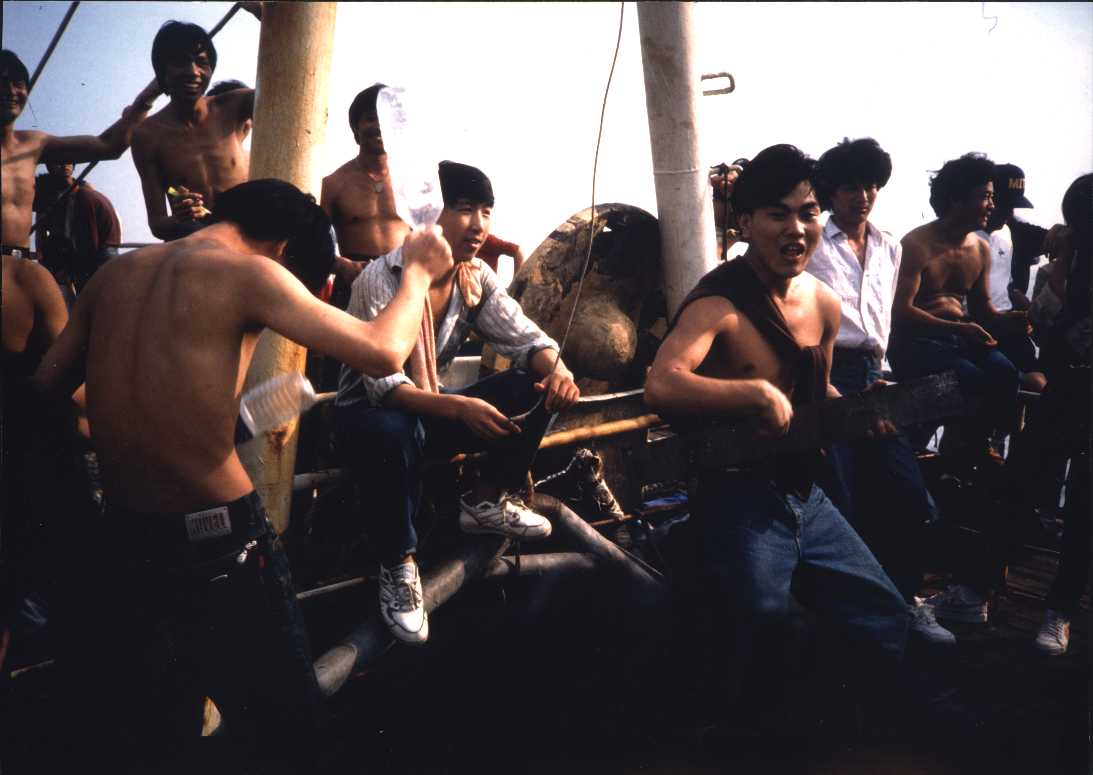

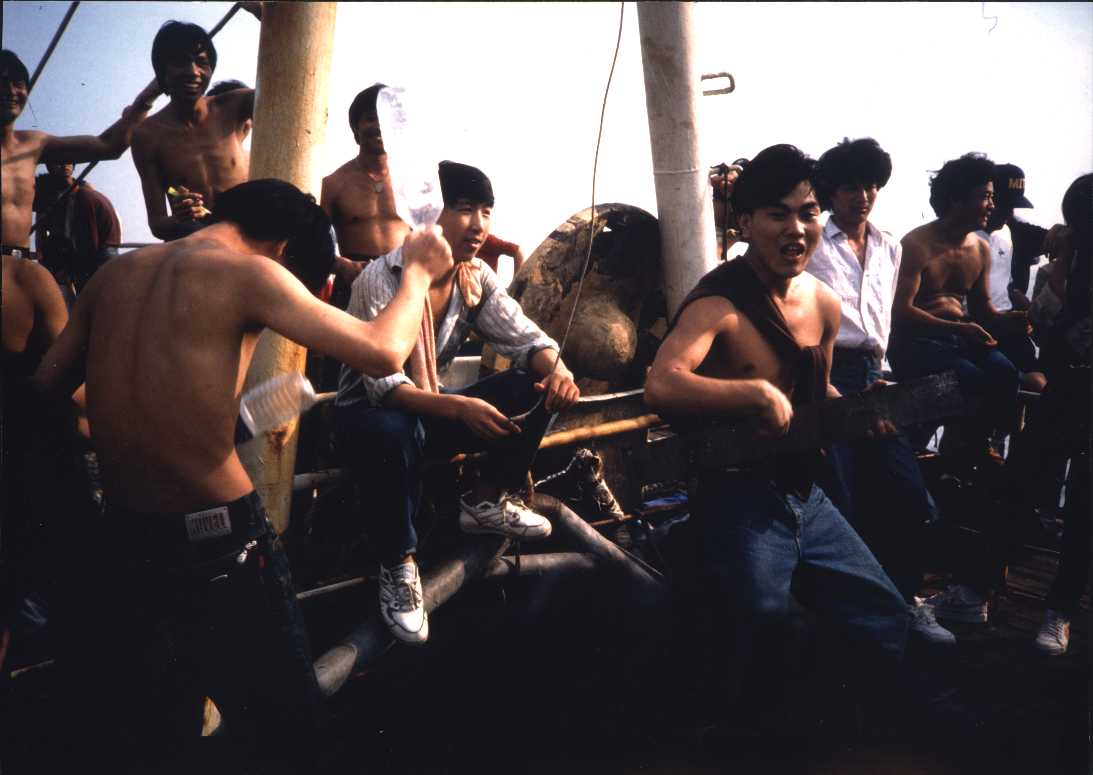

By mid-1979, an estimated 1.4 million people of all ages had fled to another country in the region. Many left over land — risking capture or being turned back at the border. For hundreds of thousands of others the only way to escape was by sea.

In recognition of the compassionate response of thousands in Canada to the needs of refugees from Indochina and elsewhere, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees took the unprecedented step in 1986 of awarding its prestigious Nansen medal to the Canadian people themselves.The "boat people" — as they came to be known — travelled for days in search of safety, often in rough seas and with little or no food and water. Many boats were so crowded that people had only enough room to sit. The vessels were generally old and small, and engine trouble was frequent. In addition to these dangers, pirates murdered, robbed, raped and abducted refugees. The number of people who perished on the seas is unknown, but is estimated to be in the tens of thousands.

Even after the refugees reached land, they faced many more obstacles. Some countries pushed the "boat people" back out to sea, while the refugee camps themselves were a stop-gap solution to a growing problem. The United Nations High Commission for Refugees worked to ensure the safety of the refugees, both on the high seas (through anti-piracy programs and guidelines for ships rescuing refugees) and in the camps. The UNHCR also helped to co-ordinate refugees' resettlement in third countries, in an effort to preserve asylum.

By the summer of 1979, resettlement had become the focus of international efforts to alleviate the crisis by reducing the number of refugees in the camps. It was hoped that this would convince countries in the region not to turn back refugees at their borders. Canada, for its part, played an important role in this process, accepting more refugees per capita than any other resettlement country at that time.

The Private Sponsorship Movement

Such generosity was a direct result of the volunteer work of people all over Canada. Most were completely new to refugee resettlement. Dozens of organizations came into being to help co-ordinate this flood of goodwill, many of which remain active to this day. This period also saw the rapid formation of a partnership between the government and the public that has been called "a golden age in Canadian refugee policy, the highlight of leadership and the highlight of dedication."

In early 1979, the plight of the "boat people"

filled newspapers and television screens. Day after day, a compelling story

was told of refugees searching for safety against incredible odds.

This unfolding drama touched the Canadian public directly. Many who volunteered

as private sponsors remember watching the televised reports in their living

rooms with tears in their eyes, feeling that they must do something to

help. As one organizer recalls, "There was all this compassion building

up and people just didn't know what to do with it."

The government, for

its part, had so far charted a fairly modest course, resettling about 9,000

Indochinese refugees between 1975 and 1978. As the international

community began to respond to the huge increase in the number of refugees

in 1978 and 1979, however, immigration officials looked to the newly created

private sponsorship program to bolster the country's commitment.

The program allowed

approved organizations or groups of at least five individuals to sponsor

refugees by providing them with administrative, financial, and personal

support during their first year in Canada. Having set the program

in motion, the government soon found itself responding to — indeed, trying

to keep pace with — an explosion of sponsorship commitments from across

the country. The recently created Private Sponsorship Program quickly

became a household term.

| "As a group of human beings we really rose to a level of excellence that we don't usually challenge ourselves to achieve." Marion Dewar |

Within a matter of weeks, Operation Lifeline was set up and had established 66 chapters across the country. Ottawa mayor Marion Dewar set in motion Project 4,000 to bring that many refugees to the nation's capital. These initiatives, along with hundreds of others got information into the communities and helped sponsors raise the funds and prepare for the arrival of refugees. The churches were particularly prominent among the over 7,000 sponsoring groups. In this process of "organized chaos," thousands of people from all walks of life came forward to dedicate their time, energy, and money.

In practical terms,

sponsorship was — and is — about more than just helping refugees find a

place to live and a job to make ends meet. It meant explaining Canada

to newcomers, introducing them to their new communities and helping them

adjust to a thousand facets of everyday life generally taken for granted.

It was also a learning experience for the sponsors, many of whom had never

before had personal contact with a non-European culture. Moreover,

in helping others, sponsors gained a better understanding of their own

country. Said one: "It gave people a little insight into their own communities

as well."

| "What was so remarkable about this time was the way that Canadians responded. And there was a tremendous response from the government as well." Flora MacDonald, then Secretary of State for External Affairs |

Seeing the momentum

of the sponsorship movement growing, the government announced in June 1979

that 50,000 Indochinese refugees would be resettled in Canada by the end

of 1980. Of these, 21,000 were expected to be privately sponsored.

All told, however, people from cities and towns of all sizes opened their

doors to more than 34,000 refugees from Southeast Asia during this time,

while the government sponsored about 26,000. Over the next two decades,

tens of thousands more came to Canada, many privately sponsored.

| One

time I crossed

The China Sea, Full of fear, In a small boat, Two typhoons, High waves Fierce winds, Death was so close. One time I

flew

From a poem by Nhung Thuy Hoang |

Twenty Years in Canada

For the refugees there were many difficult adjustments to be made. They arrived in Canada with few possessions and many memories of their traumatic escape, mixed with hopeful anticipation for the future. Most had left family behind and looked forward to the day when they might be reunited. First, however, the refugees had to establish themselves in Canada, a process that required many more changes in their lives.

The most immediate challenge was language — many remember meeting their sponsors for the first time without being able to speak to one another. The way of life in Canada also presented challenges, such as shopping for food on a weekly instead of daily basis and enrolling children in the school system. Sooner or later, everyone had to learn to live with the cold of a Canadian winter: "What I remember most about first coming to Canada was the cold! After all these years I am only now beginning to get used to it!"

| "We wanted to do something for the new country that had accepted us. We were very grateful to the people of Canada and we worked very hard to adapt to the economy and the society." Vietnamese refugee |

Before long, many had to — and wanted to — find employment, in order to regain control over meeting their day-to-day needs and to make a contribution to Canada. Recalls one refugee: "We all had come to rebuild our lives and we worked hard, sometimes two or three jobs at the same time." The desire to become self-sufficient and save money to sponsor relatives meant that refugees took on any employment that came their way, often for little pay. Some worked at the same time that they took classes to have their professional credentials accepted in Canada or get a better job in the future.

These adjustments

were never easy, but were often viewed as a necessary price to pay to secure

a better life for the next generation. Most became Canadian citizens

as soon as possible. This was not just a sign that they knew they

would not go home: it also showed that Canada had, in fact, become their

new home. Many sponsored — and continue to seek to sponsor — their

families to join them.

Twenty years later,

the presence of people originally from Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam can

be seen across the country. They have created community organizations

and have built places of worship that reflect their own cultural origins,

and become active politically, with some in public office. Hundreds

have joined the workforce as engineers, computer systems analysts, doctors,

and pharmacists. Others have their own businesses (such as restaurants

and groceries, travel agencies, autobody shops, video stores and hair salons)

or are active in international trade, while others still work in settlement

services for newcomers, using their hard-earned experience to help others

coming to Canada.

| Special

needs refugees

|

Conclusion

Today, the more than 200,000 Indochinese who have come to Canada since the 1970s are firmly established as fully contributing members of Canadian society. Through resettlement Canada provided these refugees an escape from persecution and the chance to find security in a new land. They have added new dimensions to the Canadian multicultural mosaic. They are now part of "us".

Canada's refugee sponsorship and settlement community today consists of a strong, broad-based, national network of organizations offering a humanitarian response to refugees. "Scratch the surface of many organizations involved today," it has been said, "and you'll probably find that they began in 1979, 1980, 1981 . . ." The arrival of the Indochinese refugees also helped to popularize private sponsorship, with the result that over 168,000 refugees from Indochina and other parts of the world have been welcomed into Canadian communities over the last two decades.

These legacies are clearly visible in the recent response in Canada to refugees from Kosovo. Settlement agencies quickly swung into action while people across the country, some of whom had been private sponsors twenty years ago, came forward to offer their help. Among these were Vietnamese community organizations that held fundraising events and collected donations, as well as doctors and pharmacists who, once new refugees in Canada, were now helping other refugees on their arrival. One such pharmacist explained: "I'm a boat person, so I know the agony they had to go through."

Twenty years after the Southeast Asian crisis, there are still over 12 million refugees around the world, most in the countries of the South. Dramatic though their situations are, they rarely make it to our TV screens.

For many refugees,

resettlement represents the only option for a durable solution — a chance

for life. Canada — and Canadians — can make this last chance a reality.

| "The overwhelming response of the Canadian public to the plight of the refugees gave them a sense of belonging to this country. It helped to facilitate their integration process into Canada." Vietnamese refugee | The main lesson of the Indochinese program is that voluntary sponsorship

works — and that it works exceedingly well. It provides a better

and more personal base for refugee resettlement, self-sufficiency and integration.

It also provides a clear signal to all levels of government that individual

Canadians care deeply about mass human suffering, and that they are willing

to invest their resources, their time, and their compassion to do something

about it.

Indochinese Refugees: The Canadian Response, 1979 and 1980, Employment and Immigration Canada |

Produced with the generous support of the office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees and the International Organization for Migration

Copies of the pamphlet can be obtained, free of charge from the Canadian Council for Refugees.

Canadian Council for Refugees